C is for Crisis, Cleverly Cropped

I’ve long been impressed by Starslip Crisis.

I’ve long been impressed by Starslip Crisis.

It has always had exceptional production values – clean art, reliable updates, a strong focus and engaging characters. It started out as a strip about the Starship Fuseli, a museum (in space!), and the quirky group on board – a pretentious curator as captain, an ex-pirate as the pilot, and a strangely-innocent insectoid alien as the staff. Plenty of room for humor, and that was the core focus for quite some time – and the strip continues to deliver that to this day, with a punchline in (almost) every four-panel strip. Kris Straub’s previous work, Checkerboard Nightmare, certainly got solid attention in the webcomic community – but I think Starslip is really where he hit his full stride, and delivered a masterwork.

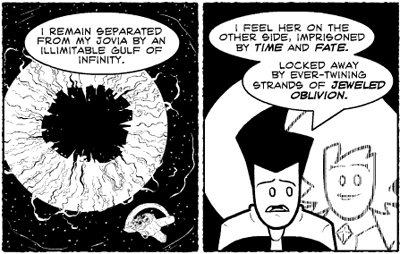

But while the initial comic was well-crafted and had a definite degree of charm, what really made it stand out was when it began to truly develop those characters… and the story itself began to take on more epic concerns. The name of the comic – Starslip Crisis – came to full meaning when it was revealed that the commonly used method of space transportation (‘starslipping’) had certain… problems. It turns out that tapping into parallel universes for your own personal convenience is never a good plan.

Events build from there. The humble crew of the Fuseli has to confront insane space tyrants, the greed-driven corporations that run the government, and an army of space-cops from the future. There was excitement, there was sorrow, there was conflict – all remarkably well-executed, all entertaining to watch.

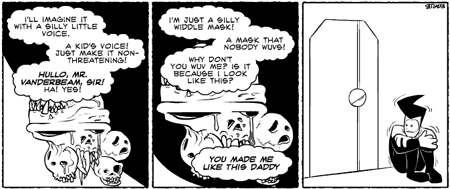

But… over the last year or so, the focus started to drift. The cast was split between several locations, and the standard interplay between the characters – which, honestly, was really at the heart of the strip – was lost. There were plenty of good moments during this time – I consider the tale of the Dreadmask to be among the funniest moments in the strip. But while Straub’s humor continued to hit the mark, the strip’s current state left him with several challenges. The storyline had gotten more and more convulated – it remained remarkably straightforward for anything dealing with time-travel and parallel timelines, but that was still complex enough to present a hurdle for new readers.

The strip had started with a wonderfully simple premise: “A museum in space.” Now, how many words would it take to describe the comic? There was no longer a single focus, nor even a single location or cast the comic was built around. Even the plot itself presented a hurdle – the present had gone to war with the future, and reached a bitter stalemate. One side didn’t have the power to hurt the other; the other side didn’t dare risk using their power for fear of wrecking their own past. How do you resolve that? Finding an answer to that dilemma was challenge enough alone.

Memnon's flair for the dramatic is often played for laughs - but sometimes, that eloquence is the only thing suitable for the occasion.

All in all, the problems weren’t large enough for me to really feel them impeding the flow of the strip – yet. The story remained potent, especially to someone who had been reading long enough to forge connections with the characters and the plot. But when Straub decided the best thing to do would be to reboot the strip, solving all his problems in one fell swoop – while also giving him an easy excuse to update the visual style of the comic – it seemed not just a reasonable decision, but an inevitable one.

Straub wrote an enlightening article on exactly what was going through his head as he took stock of his comic, why he decided a soft reset was needed for the strip, and where he wanted to go from here. The reboot itself was carried out masterfully, worked smoothly into the plot in a fashion that felt like an excellent culmination of all the recent events in the strip … even as it undid them.

The in-story justification of the reboot is that the characters escaped a dying universe by slipping into a parallel timeline – the only one they could find that avoided the pitfalls that destroyed their own timeline. More specifically – shifting them into that timeline, two years back. There are already differences, and they only grow larger as history begins to repeat itself – and just as quickly is derailed, as the crew puts their ‘future’ knowledge to use.

In doing so, they don’t just stop the plans of an insane time-traveling tyrant… but they also stop the series of events that had led to the comic growing so convoluted. No war with the future, no divided cast, no diminishing of the core concept. Indeed, it soon looked like everything would return to the status quo, and the comic could be described just as succinctly as when the strip began. And it should be noted – it would be easy to see this as rendering the events of the lost timeline meaningless, but Straub manages to keep them relevant – through the characters themselves. Because whatever timeline they are in, the growth and experiences of the characters remained intact, and could still be seen through greater competence, deeper concerns and, in many ways, a stronger awareness of their own natures.

But even with a reboot, the strip can’t stop in stasis forever. Even as Straub brings things back to the original dynamic of the strip, he did something I wasn’t expecting – and ditched the Fuseli. The space museum is retired to orbit Earth, while the crew moves on to a fancy new ship with a fancy new mission, as diplomats (in space!) It might not be the original pitch, but it remains an equally concise one. Less unique, certainly – but the comic has already established itself, and is able to stand out on already proven merits alone, rather than the need to fill an otherwise unoccupied niche. As I said at the start of this post: the strip has clean art, reliable updates, a strong focus and engaging characters – and has now shown its capacity for a well-woven and compelling plot.

So what is the point of this post? In short – taking risks can be well worth it, something I know I’ve commented on before… but nonetheless remains true. Whether evolving as an artist or being willing to change the dynamic of your strip, you shouldn’t be afraid of pushing yourself and your work into new territory. It doesn’t always pan out – a new plot might fall flat, a new style might alienate readers. But you can respond to that, and take what works and what doesn’t, and end up with something greater than it was before. If you don’t change, if you prefer to let the work sit in stasis… well, it won’t kill the comic. If it is good to start with, or even simply decent, then it is likely to remain just as decent for years to come.

And eventually, perhaps, that leads down the route of so many newspaper comics – with the strip ending up as a nice simple formula that churns out work that is entirely acceptable, but never truly exceptional.

Starslip dares to be exceptional.

B is for Belkar, Belligerently Badass

It wasn’t because Belkar was a one-dimensional character – as, in Order of the Stick, that was essentially true for all the characters in the beginning. No, it was simply due to what Belkar’s one dimension was – a homicidal jerk. A character whom the rest of the party only tolerated because… well, largely because that is what actually happens in gaming. It doesn’t matter if the rest of the group wouldn’t actually adventure with the maniac someone else decided to play – you are supposed to be a group, and find a reason for the characters to work together. So it goes.

And so Belkar got to be a bloodthirsty bastard who cared for no one but himself, and provided very little to the rest of the group (other than his natural skill at violence), and who was only really with them in order to indulge in that self-same talent. I’m sure he had his fans, but I didn’t really like the character, and looked forward to seeing him get his inevitable comeuppance.

But in the beginning, it didn’t really matter that he wasn’t a very likeable character – he was there to help serve certain punchlines, and did the job well. I didn’t need to like the character to laugh at the strip or appreciate the jokes. He filled his role well… right up until the tone of the strip shifted. As the first major arc of the strip began to draw to a close, the focus began to change from the daily punchline to the goal of an ongoing story. Humor was certainly still present… but many other goals came to the fore.

And Belkar was still just Belkar. And a character that worked well in a purely humor-driven strip was suddenly much less fitting in a comic dealing with continuity, coherency… and character development. It was, in short, a classic Bun-Bun Dilemma.

Bun-Bun is a character from Sluggy Freelance, one of the longest ongoing webcomics around – and one that has long struggled with the division between humor and story, with Bun-Bun a classic example of the potential difficulty in resolving that conflict. Bun-Bun is essentially the iconic cute by vicious little fellow – a rabbit that appears cute and fuzzy, but is all about violence and greed and self-interest, and is badass enough to actually follow through on its vicious nature. You might notice this description (aside from the ‘fuzzy rabbit’ part) almost perfectly matches Belkar – and plenty of other similar characters in other comics, cartoons and the like.

The key is, having a character with such an inherent contradiction tends to be, well… funny. The jokes practically write themselves, and such a character is a fantastic source of ongoing and reliable humor.

But once humor becomes secondary to the strip… what else is left for that character? In Sluggy Freelance, for Bun-Bun, the answer was… nothing, really. The strip has wrestled for years with what to do with the character, and found some success in casting him as an antagonist – and eventually even built up a fairly intense storyline culminating in the character being hurled out of the strip itself.

Perhaps the best possible end for the character – but, like a bad habit, Bun-Bun eventually came back… even though there really was no good place for him. He couldn’t be given any character development – it would have gone against his very concept. The only role left to him? To randomly show up, utter his usual threats and insults, recall the same tired jokes that he was created for… and then step offstage again.

And this was the future facing Belkar.

Don’t get me wrong – these characters have plenty of fans. Bun-Bun’s legions of followers will endure long after the rest of Sluggy Freelance is forgotten, I imagine. The concept is more succinct, more marketable, more independant than the story the character was placed in – and that’s why the evil little ball of fur will keep showing up long after the comic has actually had a use for it. Similarly, many have been fans of Belkar despite his self-serving and homicidal tendencies. I imagine many have been fans of him because of it.

Which is where the dilemma comes in. How do you keep the character in the strip when having their development keep pace with the rest of the story would destroy the very essence of the character – the very elements that all their fans care about?

The approach in Sluggy Freelance was to make Bun-Bun an adversary, and Belkar could easily have fallen into that role – except that part of the character’s core was being one of the PCs. So a solution needed to be found that would let him remain a member of the party, despite the fact that no sane group would truly keep him around longer than they had to.

Fortunately, it is a comic in a fantasy world, which means “A Wizard Did It” is a perfectly acceptable means of finding a solution to a problem. Belkar gets tagged with a magical curse to reign in his murderous capabilities, and keep him working with the party – still free to spout insults and be his usual charming self, while allowing him to legitimately function as part of the group.

An elegant solution… but not a permanent one. The rest of the group was continuing to develop and fit into the story, while he was just being dragged along, more of a plot hook than an actual character. Which is when the comic’s esteemed author, Rich Burlew, began the real challenge – finding a way to redeem the character. Finding a way to make him truly part of the group, a character who both had reason to work with the rest of the group, and was someone whose presence they would welcome in their midst.

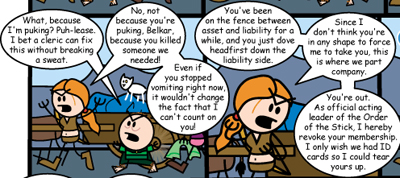

Over the last fifty or so strips, Belkar’s tale has unwound, as he is taken as low as he can possibly go – crippled by the curse upon him, the others finally realizing the want nothing more to do with him, and… oh yeah, a rather dire fate awaiting him.

Now, with most characters, this would be the perfect opportunity for redemption. For the character to realize that they only got this far through the help of their companions, and that living a life based on selfishness and impulse has only left them cursed, friendless and alone. And the character would rise up, having learned The Meaning of Friendship, and put their conflicted past behind them!

But… Belkar has no conflicted past. He has never wrestled with any moral dilemmas. Immoral ones, sure – but there has never been the slightest bit of selfessness in his character. Having him become a decent fellow would be a complete contradiction with the very core of the character!

Yet Rich figured a way out. You don’t have to be Good in order to perform Good acts – you just need a good enough reason to do so. Belkar learned that lesson before, when he saved a paladin from an assassin in the hopes of getting his curse removed.

Rich might not be able to change Belkar’s self-interest, his greed, his lust for violence… but he could change his

impulsive nature and his antisocial tendencies. Belkar, crippled by his curse, barely hanging on to consciousness, reaches an epiphany – he doesn’t have to actually follow the same moral code as his companions, he just needs to fake it. He calls it “faking character development” – but the development is there, just not what was expected.

It’s a realization that he can get farther in the world if he has people who can – and will – watch his back. All he has to do is give them reason to keep him around – which he can already do, due to his skill with a blade – while not giving them reason to kick him out. Which does mean he needs to refrain from murdering anyone who momentarily pisses him off, and cutting back on being completely abrasive to the rest of the group – but in the long run, he realizes, it is worth it. And given the life of an adventurer, he knows he will have plenty of foes whom he will not just be allowed to butcher to his heart’s content – but even rewarded, even celebrated, for doing so.

He has successfully known character growth. Not from a villain into a hero (or even an anti-hero), but from a wild, erratic murderer driven by little more than impulse… into something resembling a magnificent bastard. As long as he acts with style and stays a team player… well, it has already paid off so far, in spades.

And it makes him interesting. And it lets him keep his spot in the party, and keep his role in the story. And it makes him, despite his nature, someone the good guys can cheer for. I may have hated him throughout his career – but when he hopped to his feet and started eviscerating rogues, demonstrating his sheer level of badassitude, on behalf of a righteous cause… well, I was rooting for him all the way.

We’ll see whether he can carry this out indefinitely – violence might solve most problems in an adventurer’s life, but not all. I’m sure there will be times when putting up with the moral outlook of the party might be a challenge – but then, conflict is the core of a good character. And – in many ways now more than ever – conflict is what Belkar is all about.